Interview with a Book Designer: Jazmin Welch—Part One

Connections Between Publishing and Fashion, a Masters Degree in Publishing, and Making Freelance Finances Work

Why books?

When I interview other book designers, this is among the first questions I ask. Because on paper—70 lb uncoated text stock, that is—it isn’t exactly the most logical career choice.

For starters, book design is not the most lucrative profession. If you’re a graphic designer and like money, I have a few other recommendations for you.1 It is also something of an opaque sector of a largely centralized industry that doesn’t offer many apparent in-roads. When I got started in this business, my main goal was to figure out how to do this without moving to New York City. At the time, I wasn’t sure if it was possible.

To become—and stay—a professional book designer, you must really want to design books.

I’m proud to be one of those freaks. And I love talking to the others. This week, I’m excited to share a new installment of Interview with a Book Designer.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Jazmin Welch is a book designer, the owner of Fleck Creative Studio, and the cofounder of The Book Designer Collective.2 She runs her business out of Hamilton, Ontario, where she produces artful book design and shares an absolute wealth of knowledge for authors and fellow designers alike.

We sat down this summer for a virtual chat to talk about her career, the relationship between fashion and typography, the differences between Canadian and American publishing, and, of course, money.

Nathaniel: Before we begin, I thought it might be entertaining for you to learn how I stumbled upon you and your work. About two years ago, I was randomly looking for book design content on the internet. I opened up my Apple podcast feed and literally just searched “book design”—and I came across your episode of the The Print Design Podcast. Do you remember doing that show?

Jazmin: Yeah! That’s wild.

After that I thought, “Fleck Creative, she’s cool!” And I looked you up on Instagram and gave you a follow. And now here we are, both part of the The Book Designer Collective you started, and having this chat. I listened to it again last night to try and make sure you don’t repeat yourself.

That’s funny! That was my first time doing any kind of interview—and my biggest thing after watching was like, “ooh, I gotta laugh less.” [laughs]

That’s why this isn’t a podcast. OK. First question: Of all the things you could design, why books?

That’s a good question. I started in fashion design, oddly enough. I went to school at Ryerson (now Toronto Metropolitan University) for fashion communications and I always thought I’d be a fashion illustrator, sitting at the end of a runway doing live fashion drawings. But as I was studying fashion, we started doing typography, and I really fell in love with magazine design and editorial layout. Placing things on a page and convey meaning based on that placement. So, I actually came to books more from an interior perspective rather than covers.

You’re popular! You’ve done a few interviews, so I don’t want to make you repeat yourself too much. I read one from collabs.io Mag in which you bring up those fashion origins. How does typography relate to fashion for you? How does that fashion experience impact your book design practice?

From a very linear perspective, fashion needs to be branded. So instantly you’re looking at hang tags, the labels, the brand of the whole universe of a clothing line. And then that leads to how it’s marketed out in the world both from the company itself and in editorial. That was a very minor part of the fashion program, but I think a lot of us hung on to it because it has such vast implications in the world.

Marketing became not something I really wanted to get into exactly, but all design is communication. That’s what book design is, too. When you create something with type and color, you’re saying something to the world. You can apply that to anything. We studied advanced color theory in courses that weren’t even necessarily focused on fashion. So I think the program really set us up well in the design world at large.

To circle back to “why books,” as a kid I just loved paper. I think a lot of people who end up in book design are paper people, tactile people. And maybe that’s a relation to fashion, too. It’s a very tactile form to be working in. I love working with my hands. I love actually creating things like sewing—similar to you with collage and things like that, even though I’m terrible at collage and would love to improve upon my collaging skills.

You just gotta do it! I’m working on a newsletter about collage being the best introduction to becoming an artist, but I haven’t quite cracked it yet. So look for that. I’m going to try to convince you that all you need to do to be an artist is make a collage [laugh].

I believe wholeheartedly that adults—we just stop ourselves because we don’t have that kid brain anymore. No kid is walking around at age three, four, five, saying “I can’t draw.” They’re just innately drawing! I love that about the idea of cutting things up and putting them down. I had a teacher who was very much like “analog is how you’re going to become a good designer.” Get off your computer, take a step back, and get moving with your hands.

Oh yeah. I think all of the growth I’ve had as a designer has come from a merging of analog and digital. When I was in university—to borrow the Canadian phrase—I was very digital-only. I had taken like one art class in high school, thought I couldn’t draw, and got started by tinkering around with my dad’s copy of Photoshop Elements. I think the more I’ve integrated both physical and digital, the stronger I’ve become as a designer.

Back to fashion—this might be cliché, but one thing I’ve heard and like to say is that a typeface is sort of like the clothing of words.

And also personality too, right? Each type has its own personality and that’s how you pair fonts. One of the things that’s so interesting about design that definitely applies to fashion, too, is that you can take something from a certain era—like a font that looks vintage—and remix it with colors and other visual elements and you’ve suddenly made something that doesn’t look vintage anymore. That’s why graphic design and fashion are so interesting: there are endless possibilities.

In addition to this fashion background, you have a Masters in Publishing degree—which I find fascinating because I’ve become such a publishing nerd. But everything I’ve learned about the industry has sort of been bit-by-bit as I clawed my way in. How did that degree prepare you for this work? Looking back, would you say it was worth it?

When I was deciding whether or not to pursue the Masters, I was self-employed and had just quit my entry-level marketing job. The job was fine, but I wasn’t doing creative work. When I moved into self-employed life, I actually connected with a book design agency even before starting my journey into that world. So I did my first few books—it was all self-taught, as I think most of us are—and figured out how to put stuff into InDesign. I had a basis for how the program worked, but not how to string together a whole book. My first book was about mortgages, which is kind of funny. It was such a great learning experience—but it also showed me how little I knew.

I started to apply to a few presses, and I was not getting any of those jobs. I was like, “what am I doing wrong?” So I went on LinkedIn and looked around to see what credentials I might be missing. And the designers I found all seemed to have the Masters from Simon Fraser University. I knew I wanted to be in the world of books, and if I was going to go back to school, it was an all-or-nothing thing. So I decided to move to Vancouver.

I will say: I wanted to drop out immediately. In the first week, we were basically taught how to open InDesign. This is because the students in the program come from a range of backgrounds and most are not familiar with graphic design software, so we had to start from the very beginning.

Oh no.

I was like, “this is a lot of money to be paying to learn how to open InDesign!” I think there was some miscommunication in the application process (which is feedback I gave to the program), so unfortunately a lot of the listed prerequisites that I prepared to get into the program, turned out to be skills that would be repeated in the program itself. This cause some aggravation on my end. So I was immediately thinking, I’m out!

Despite sitting in the design course that served as an introduction to things I studied in my undergrad and software I had been using for years, the design professor was extremely knowledgeable and insightful (she's the one that urged us to play and explore by hand before moving digitally) and allowed me to do a few self guided projects to ensure I was learning something new. In the end, I do think it made me a stronger designer, and I’m glad I stuck it out. Ultimately, the best part of the program was learning the inner workings of a publishing house. What actually happens there; what’s the actual hierarchy; how does a book move from point A to point B. And I don’t think you get that understanding necessarily as a freelancer because you’re not in-house. I do think that was extremely valuable.

And also, the editorial process. I knew nothing about how many rounds of editing you go through. We had to edit a book while we were in the class—which is so not my strong suit [laughs]. But it was a good experience!

And I imagine it helps you work with other people who are good at that.

Exactly. Another thing I felt it was important to know was the state of the industry. Where things are going; troubles with the industry. There’s so little transparency in publishing so it was very interesting to see how backwards and out of touch it can be. Book prices are not going up, wages in the industry are not going up. You need to know how things are working in order to do things differently.

These lessons from the program were interesting, if a little depressing.

It sounds like it wasn’t very helpful for design but helped you gain a more holistic view of an industry that can be kind of opaque if you’re not inside it already. That’s cool—as far as I know, I haven’t heard much about publishing degrees specifically. You hear about a lot of people with english or marketing degrees.

I learned a lot of very important things about technology in publishing and the history of publishing. But fellow book designers have asked me “will this help my design career?” And I am like: “Dicey.” [laughs] It’s not intended to be a design program so you must have a strong desire to learn more about all aspects of publishing. But I will say, that because I finished the degree, I think it really helped me get my job at Arsenal Pulp Press. Everybody there is a SFU MPUB (Master of Publishing) grad.

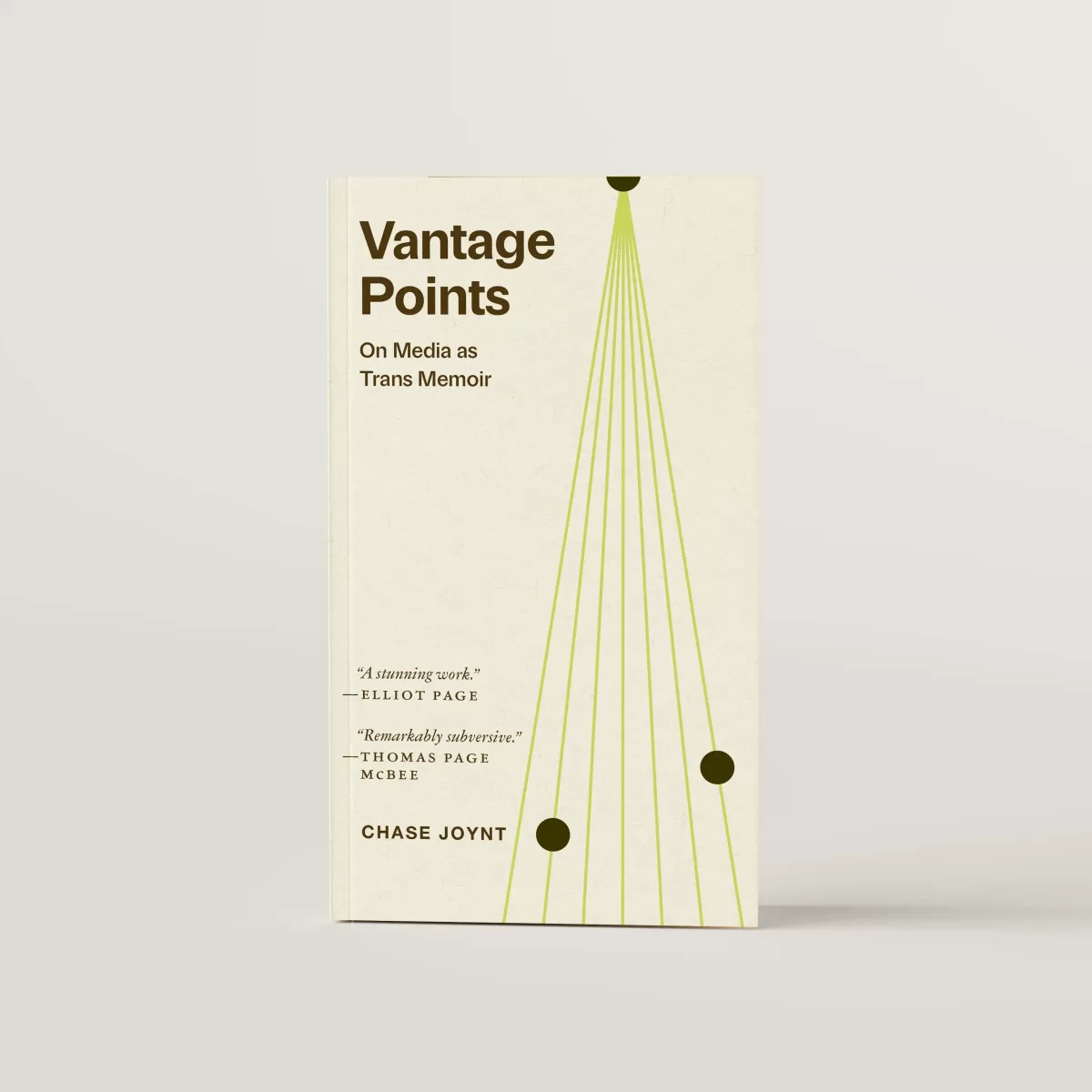

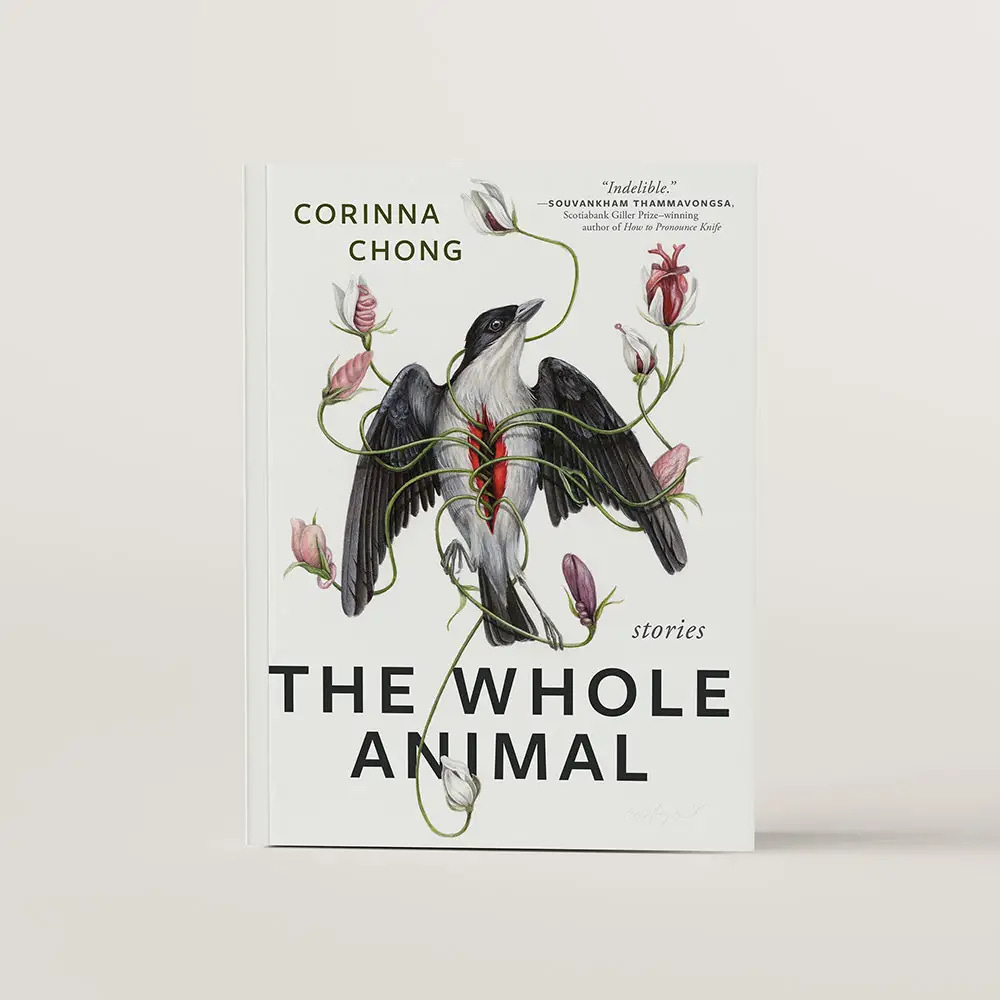

This leads me to one of my next questions—I see you posting about Arsenal all the time and I wasn’t sure if you freelanced for them or were in-house. So, you’re on staff there?

Not anymore. I started on staff there after I wrapped up my program, and I never fully dropped my freelance business while I was there. And then COVID hit. And I got a dog [laugh].

—Emma, right?

Yes!

So that changed things for me a little bit. I wanted to maintain more of a flexible schedule, and it was such a low-paying position—which is not a surprise to anyone in the industry—I was just really struggling to live in Vancouver. I was blowing through my school savings in order to be a working professional. So that’s when I asked if I could move the job into a contracted position so that I can continue my freelance business. But I love the work that I get to do for Arsenal.

That sounds like a really sweet gig, and it’s cool they were so flexible about the nature of that relationship. And I love the work you do for Arsenal, which drove my curiosity. My big question for this series is “how do you make this work?”

Speaking of that, I want to get to the juicy part of this interview where we talk more about money. It was so refreshing to talk to Jordan Wannemacher about that—I was like, “oh, that’s what this is about.” I didn’t realize that when I started this but I am so curious about how people make it work financially and if full-time freelance is possible for book design.

It’s not the most lucrative profession, or sector of graphic design, and on top of that, you work with a lot of self-published clients that have variable budgets. All of that to say—how do you make freelance finances work? Answer as broadly or specifically as you like.

A big piece of that is working at Arsenal Pulp Press. I am the “in-house/out-of-house” book designer there so they are my biggest client and my priority. It’s a lucky situation to be in. I know I need to make X amount of dollars from my other various freelance gigs in order to, you know: support that dream of home ownership one day, actually be able to save on a monthly basis—and I know that’s such a privilege these days—but that’s what I am working towards.

My income has been pretty stable for the last three years. I feel way less worried about finances than I have previously. And I have raised my prices, which for the most part has not come with any backlash from current and new clients.

That means you didn’t raise them high enough. [laugh]

I do get that feedback sometimes! Some people who are in my orbit, who know what I do, but have come from other worlds are all like: “Oh my god, you charge nothing! How do you live?”

I will say I am a bit of a nut about spreadsheets and doing all of my accounting that way. I use accounting software, but I do constant weekly recaps that chart how many books I need to do to reach a certain dollar amount. A few years ago I did a “master break down” of where I want my finances to be and how many books I want to work on to be comfortable without overworking, and then doing a division to see what the per-book rate needs to be. For me, that ended up being around $3,000 (CAD). Which sometimes feels way too low, and sometimes feels perfect, depending on the project. But if I can net out around there, then that feels good for me.

And that’s for full book packages usually, right?

Right. Full cover and interior. For a novel—nothing with pictures, not a full coffee table book.

I do find that sometimes you work with a publisher who just presents you with a budget and are like “here’s what we’ve got, take it or leave it.” So that can be tough. I was presented with an offer for $700 for a cover. And the book sounded great, and as book people there are so many times we say yes to projects that are not financially fulfilling whatsoever because we love the work, but covers are still a ton of work for that rate!

Yeah … I do that probably too much. Because you’re right, I’m such a book person. Like, your book sounds great, and I have ideas! And I’m too excited about those ideas. That’s part of why I’m not sure if I could do freelance full-time because I accept $600 cover projects for books that interest me. It feels like all of my interests are the least profitable things in the world [laugh].

I do think you can get more money than you think from self-published books, though—not that we’re gouging anyone by any means. There are just a wide range of budgets out there which include folks with deep pockets—those with corporate jobs or rich spouses [laugh]—who are out there doing interesting passion projects! It can still be really interesting content that people have invested interest in sharing with either friends and family or a wider audience. And many of these folks respect you as a professional when hiring you for your book design services so they pay accordingly to rate they’re more familiar with, rather than the low publishing industry rates.

What’s the highest you’ve been paid for a book or book cover? Alternatively, what’s the lowest? I love knowing that range because usually, it’s wildly different.

If you like editorial and can land an annual report, those are usually higher paying. Those are often like $5–10,000. My biggest project was a textbook that just got out of hand so I don’t even know if this relates! I went on an hourly rate because the process just got so messed up (think copyediting happening after 700 pages are laid out). I think that project netted close to $10,000 if not more, maybe $12,000. The hours on that project were insane.

It’s funny—when I asked Jordan that question, her answer was also a case of scope creep that she then had to charge more for.

I’ve told this to family and friends when complaining about really tough projects: When a project reaches that point, it’s not even about the money. I just want my time back. I want the project to be done. Usually by that point you’re not working on the creative part anymore, you’re not having a blast and you’re likely bottlenecking all of your other work, working late and feeling perpetually behind on everything.

You’re crawling through the mud at that point.

In terms of lowest—I think I was charging, like, $300 a while back (for a cover). I don’t think I would do one for $300 now. I do believe in doing volunteer and pro bono work, but if the project isn’t pro bono, I wouldn’t want to go below $500, unless it’s something I am just obsessed with and want to be a part of, whether it’s because the book relates to a cause I believe in, something I care deeply about, or it’s a project that I know will fuel me creatively and add something completely unique to my portfolio. While I wish publishing was a more lucrative endeavour for everyone involved, I think most of us book designers just really really love what we do and care about our work, so the math on the hours we spend diving into a design don’t always add up to what we get paid, and I think that’s ok sometimes. At the end of the day, I do feel extremely lucky that I get to design books for a living.

End of part one.

Thank you for reading! This was part one of my conversation with Jazmin Welch, and there is a more to come. If you enjoyed this, consider subscribing and stay tuned for part two.

If you would like to support A Book Designer’s Notebook, consider buying me a “coffee” or becoming a paid subscriber. Paid subscriptions grant you access to exclusive, themed chats with myself and a growing community of book design lovers.

If that’s not possible, a like, comment, and share go a long way toward getting my work read. I’d appreciate it.

Until next time,

—Nathaniel

Colophon

A Book Designer’s Notebook is a newsletter about books, design, and creative practice from the desk of Nathaniel Roy.

It uses the typefaces Merriweather, Futura, and whatever fonts Substack has chosen. Merriweather is a Google font designed to be a text face that is pleasant to read on screens. Futura is geometric sans-serif designed by Paul Renner in 1927. It is on the moon.

Nathaniel Roy is a book designer, collage maker, photo taker, self publisher, and a few other things in Ypsilanti, Michigan.

You can see his work and hire him here.

More Like This

Not newspaper design, though. I would know.

Of which this author is a part.

This is such a great interview and behind-the-scenes peek into an area of design that I know very little about. Thank you!

Hang with me long enough and you’re likely to hear me say, “everything feels the same under glass.” The sameness about reading on our phones, the dullness, the eye-stabbing boringness of it all after a while.

I recently gave a copy of my latest legacy book to someone and he caressed the cover and said, “I love how your books feel.” I know he won’t read it because he’s not a reader, but two things that make my heart swell and make me immediately crush on you is when you 1) caress a book cover and/or 2) open a book and smell the pages, breathing in the ink and dust and paper in a long drag that you release slowly into the air with a satiated face.

A digital world ain’t it. Analog. don’t only touch grass, but touch some paper, run your things across some deckle edges, smell the endurance of it from an old book.

*Posted as a note before I realized I was not posting a comment. 🤷♂️